Today the Livingston Awards honor stories that represent the best in local, national and international reporting by journalists under the age of 35. The winning stories uncovered text messages indicating Mississippi’s misuse of federal welfare funding, the inner working of the U.S. government’s child separation policy, and the atrocities committed by Putin’s army against civilians in Ukraine. The $10,000 prizes are for work released in 2022.

The Livingston Awards also honored Ken Auletta, author and writer for The New Yorker, with a special tribute for his enduring commitment to the Livingston Awards and the careers of young journalists. Auletta joined the Livingston board of national judges in 1983, the third year of the program, and served in that role through 2022.

Livingston Awards national judges Sewell Chan of The Texas Tribune, María Elena Salinas of ABC News and Matt Murray of News Corp introduced the winners at a ceremony hosted by former Livingston Awards national judge Anna Quindlen, author.

“The best reporters keep looking, questioning and documenting when they are told there is nothing more to see,” said Lynette Clemetson, Livingston Awards director. “This year’s winners laid bare abuses of power and the networks of complicity and complacency that allowed those abuses to unfold. Their work influenced the public record and how history will regard the players and their deeds. It is an honor to recognize them for their tenacity, rigor and storytelling excellence.”

Today’s ceremony included special remarks from Matthew Luxmoore, a Livingston Award finalist and reporter from The Wall Street Journal who covers Russia, Ukraine and the former Soviet Union. He spoke at the podium in support of his friend and colleague, Evan Gershkovich, who has been wrongfully imprisoned in Russia since March 29 of this year.

Celebrating its 42nd year, the awards bolster the work of young reporters, create the next generation of journalism leaders and mentors, and advance civic engagement around powerful storytelling. Major sponsors include the University of Michigan, Knight Foundation, the Indian Trail Charitable Foundation, the Mollie Parnis Livingston Foundation, Christiane Amanpour, the Judy and Fred Wilpon Family Foundation, Dr. Gil Omenn and Martha Darling and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

The 2023 winners for work released in 2022 are listed below.

Local Reporting

Anna Wolfe, 28, of Mississippi Today for “The Backchannel: Mississippi’s Welfare Scandal,” a multiyear investigation into Mississippi’s 2% approval rate of applicants for federal welfare funding uncovering text messages between then-Governor Bill Bryant, state officials and Bryant’s friends, including NFL football legend Brett Favre and unraveling the largest public fraud in Mississippi’s history.

“Anna Wolfe’s dogged investigation into Mississippi’s misuse of funds intended to help needy families demonstrates the power of journalism to expose corruption. She was the first to reveal text messaging indicating that welfare funds had been diverted to a pharmaceutical company in which a retired NFL star was an early investor. Her tenacious digging, over multiple years, has had a staggering impact on a state with high levels of poverty and inequality.”

— Sewell Chan, Livingston Awards national judge

National Reporting

Caitlin Dickerson, 33, of The Atlantic for “We Need to Take Away Children,” a masterful examination of the U.S. government’s child separation policy revealing how officials at every level heedlessly and often deceptively advanced policy that defied the country’s most basic stated values.

“In her exhaustive reconstruction of the Trump administration’s implementation of its family separation policy, Caitlin Dickerson brought to life jaw-dropping and eye-opening details of how the policy was accepted and implemented at different levels of government. Through exclusive interviews at multiple levels, she meticulously laid out how a handful of people set off a chain reaction of chaos and pain that continues to this day. Her reporting has established a new public record of a devastating episode in our nation’s history.”

— María Elena Salinas, Livingston Awards national judge

International Reporting

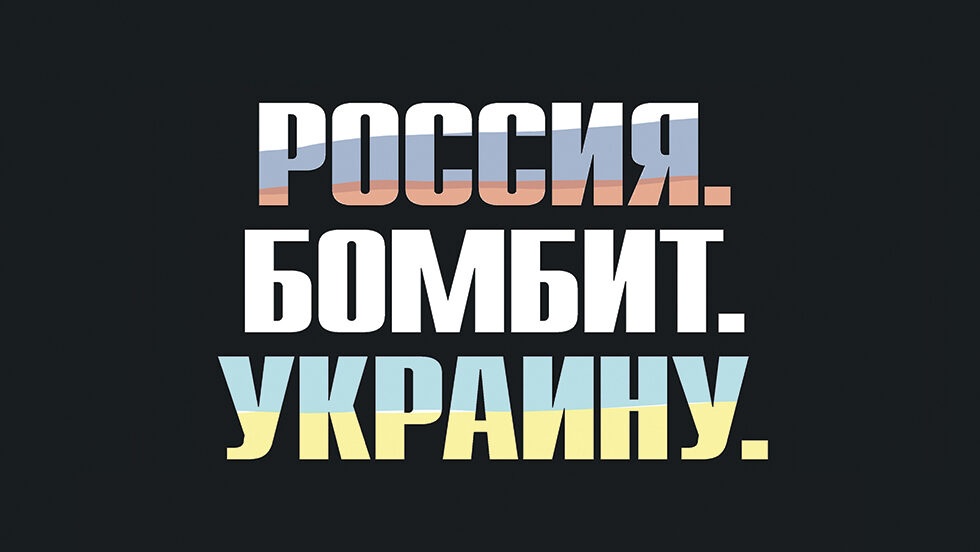

Vasilisa Stepanenko, 22, of The Associated Press for “A Year of War,” a series of harrowing videos exposing the atrocities against civilians committed by Putin’s army in Ukraine and laying bare the devasting human toll of war.

“In a year that saw a great deal of amazing and powerful work from journalists covering the Ukraine war, Vasilisa’s stories had a unique immediacy and visceral power that vividly bore witness to the impact of the war in her country. Her work had an undeniable impact on the world’s understanding of the struggle. And the great personal courage she displayed amid tremendous peril underscores the stakes of the battle to tell the truth on the ground.”

— Matt Murray, Livingston Awards national judge

Special Tribute

Ken Auletta, author, media and communications writer for The New Yorker and Livingston Awards judge from 1983 to 2022.

This year the Livingston Awards honored Ken Auletta with a special tribute for his enduring commitment to the program and the careers of young journalists. Anna Quindlen, author and Livingston Awards judge from 2009 to 2022, presented Auletta with the award and introduced a video with tributes from his fellow Livingston Award judges and past Livingston award winners. Kara Swisher said in the video tribute, “There’s an expression. Anything that can shine does. Ken shines a light on the things that shine, which is really important when it comes to young reporters.” Auletta’s most meaningful legacy is in the lives and careers of journalists he helped transform.

Watch the video tribute to Ken Auletta.

In addition to Chan, Murray and Salinas, the Livingston national judges panel includes Raney Aronson-Rath of PBS; Audie Cornish of CNN; Lydia Polgreen of The New York Times; Bret Stephens of The New York Times; and Kara Swisher of New York Magazine.

More on the winners here.