BY ANNE CURZAN & CELESTE WATKINS-HAYES

On a Monday evening in late November, throngs of University of Michigan students, faculty, staff,

and Ann Arbor residents waited expectantly outside the Michigan Theater to attend the

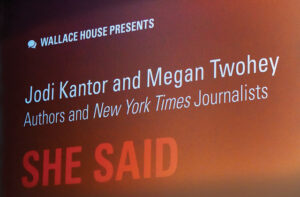

premier showing of the film, “She Said.”

The movie chronicles the reporting of New York Times journalists Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, credited with successfully revealing decades of sexual misconduct by film producer Harvey Weinstein and igniting the #MeToo movement. When the film ended and the two reporters walked onto the stage, the packed audience stood for an extended standing ovation and students lined up in the the aisles to ask questions.

In March, campus and community members converged again, this time at Rackham Auditorium, for An Evening with CNN Anchor Chris Wallace and Governor Gretchen Whitmer, with an opening welcome by U-M President Santa Ono. Hundreds of student tickets were claimed within 15 minutes, despite the fact that the students were on spring break when they were announced. Whitmer and Wallace engaged with each other and the audience on topics important to the student body—from gun legislation in Michigan, to funding for mental health services on campus, to the responsibility of media to combat disinformation and to allay, not fuel, polarization.

The two events were quite different. But each featured journalists prompting incisive conversation on difficult topics across points of social and political difference. As deans of the School of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA) and the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy respectively, we take seriously our responsibility to serve the public good by bringing diverse groups together to grapple with important issues. Through these conversations, in partnership with the Wallace House Presents series, it is our hope that we all might be inspired and energized to make positive change in our communities.

One of the many remarkable things about the University of Michigan is the caliber of public events that the university sponsors on campus and in the community. Together we lead Democracy & Debate, a university-wide educational initiative that encourages students, faculty, staff, and community members to explore the exchange of ideas and free speech; the responsibilities of members of a democratic society; structural inequalities in our democratic systems; the power of the individual voter; and democracy from a local to a global perspective. Now finishing its second year, it has prompted projects and collaborations spanning numerous departments and disciplines.

Universities are central to thriving democracies. Journalists and journalism are essential as well. Excellent works of journalism bring facets of enormous, unwieldy issues into sharper focus. Rather than accepting that the stories we see, hear and read every day function as mere background noise or posts to scroll past, scholars and journalists share a desire to capture people’s attention with evidence, analysis and humanity and to turn consumption of information into a conscious act.

Democracy & Debate and Wallace House Presents are well- suited partners in this endeavor. And it has been gratifying to bring our scholarly and journalistic styles together for interesting pairings.

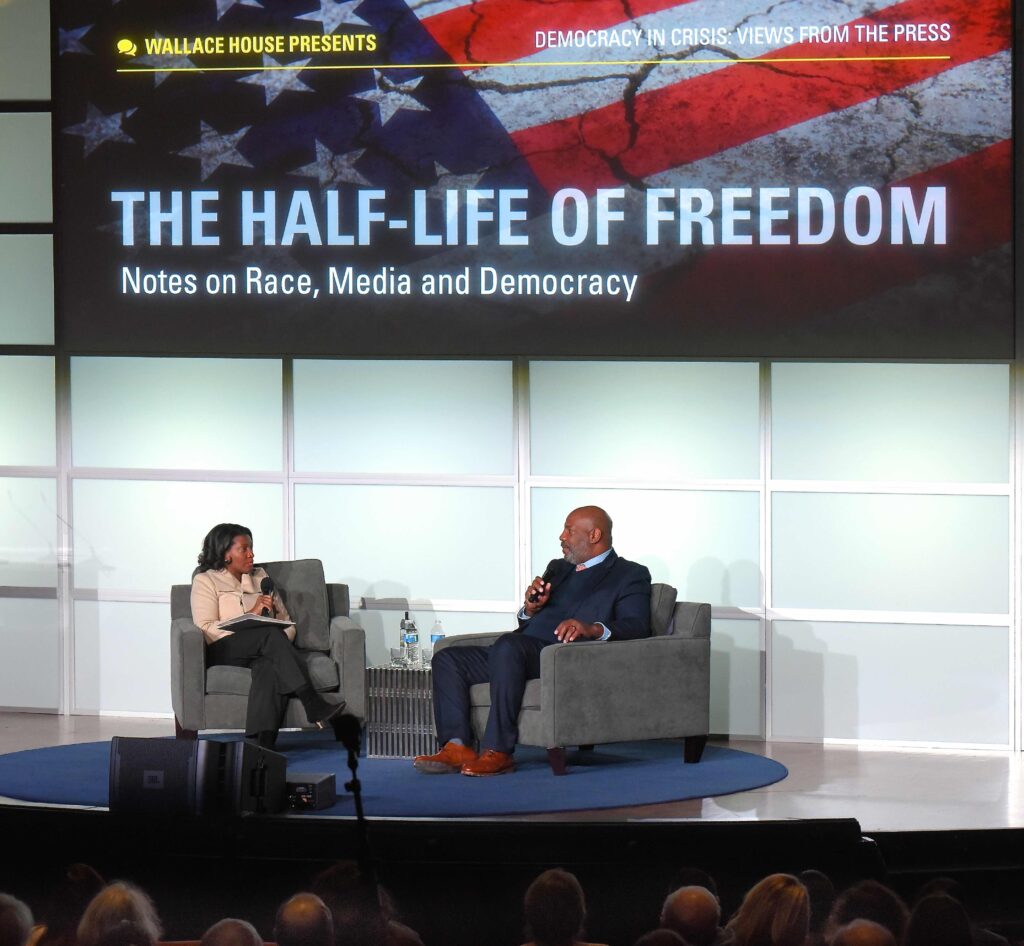

Celeste, who founded the Ford School’s Center for Racial Justice, interviewed Jelani Cobb, dean of the Columbia Journalism School and staff writer for The New Yorker. The conversation, titled The Half-Life of Freedom: Notes on Race, Media and Democracy, examined how historic challenges to democracy are reflective of a long history of fissures and contradictions in our democratic ideals.

From his unique vantage point as a journalist and historian, Cobb powerfully reminded us that the question of who America is for has yet to be resolved and that U.S. social justice movements are collective attempts to challenge our country to live up to its democratic ideals. He took a topic that could intimidate and distance an audience and provided relatable points of entry and even humor.

Anne, a linguist and host of the weekly podcast and Michigan Radio segment on language, “That’s What they Say,” interviewed journalist and best-selling author Anna Quindlen about the importance of personal writing. While the discussion focused on Qundlen’s book, “Write for Your Life,” the conversation captured the fundamental role written language plays in shaping not only our individual experience, but our history and collective memory.

The lively exchange urged audience members increasingly conditioned to process their days through texts to consider the long-term value of contemplative daily writing—whether in a journal, on a notepad, or in a phone. Quindlen, with all of her accolades as a writer of fiction and non-fiction, was wise, funny, and deeply human, as she shared with us the joys (those “aha!” moments) and challenges (reading feedback from editors) we all face when we put words to paper, whether we are students or professional writers.

The goals of the Wallace House Presents series are to highlight the vital role journalists play in our society; to bring transparency to how journalists pursue their work; to extend the reach of the issues they examine; and to foster civic engagement and civil debate—on campus, in the classroom, and in the broader community.

These goals resonate with key aspects of both our schools’ missions: the rigorous pursuit

of knowledge and truth; the humanizing of large-scale problems, as well as the process of understanding and addressing them; the commitment to democratic values, including academic freedom and the freedom of the press; and respectful, well-informed debate.

As deans, we worry that the issues we collectively face are so big and so pressing that people

will become numb to them. Difficult topics are so loud in our rapid, repetitive information

cycle, that people can inadvertently, or self-protectively, stop listening and thinking about them.

But our experience with university events demonstrates that, when given meaningful opportunities, people lean in and engage. The “She Said” screening, which was also co-sponsored by the Office of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion and the College of Engineering, drew one of the largest audiences the Michigan Theater had seen since before the pandemic. We were particularly inspired by the number of women student journalists who asked questions about how to use journalism to effect social change and how to navigate the numerous assaults on the profession. The event was one of the most memorable evenings of both of our academic years.

We are grateful to work alongside Lynette Clemetson and the Wallace House Center for Journalists to bring signature events like these to campus. And we look forward to continuing the important work of ensuring that democratic ideals, principles, and institutions continue to thrive on the University of Michigan campus and beyond.

Anne Curzan is dean of the University of Michigan’s College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and serves on the Wallace House Executive Advisory Board.

Celeste Watkins-Hayes is the Joan and Sanford Dean of the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, founding director of the school’s Center for Racial Justice and serves on the Wallace House Executive Advisory Board.

This article appeared in the Spring 2023 issue of the Wallace House Journal.