This article appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of the Wallace House Journal.

Q&A with Anna Clark of ProPublica

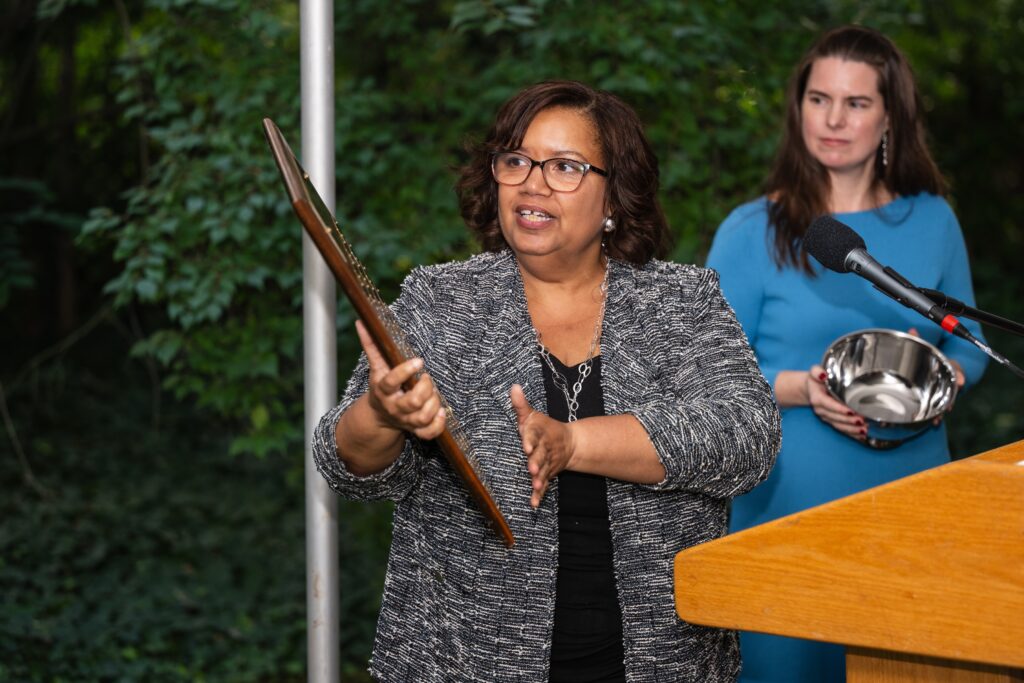

The annual Graham Hovey Lecture was started by Charles Eisendrath in 1987 in honor of his predecessor Graham Hovey, director of the fellowship program from 1980 to 1986, to recognize a Knight-Wallace journalist whose career exemplifies the benefits of a fellowship and whose ensuing work is at the forefront of our national conversations. This year we welcomed Anna Clark, a 2017 Knight-Wallace Fellow and currently a journalist with ProPublica living in Detroit. She is the author of “The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy,” which won the Hillman Prize for Book Journalism and the Rachel Carson Environment Book Award, and was longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction. She is a nonfiction faculty member in Alma College’s MFA Program in Creative Writing and was also a Fulbright fellow in creative writing in Kenya. Anna sat down with director Lynette Clemetson to discuss the dangers of a culture of secrecy and what it takes to push back.

Q: When I raised the idea of government transparency to you as a possible topic for your Hovey Lecture, I was concerned that you might think it was too wonky, but you were all in.

A: Freedom of information and public disclosure policies are part of our architecture for democracy and justice. I’m very passionate about it.

Q: Many people don’t know that Michigan ranks low in some areas of transparency.

A: I love this state, but I am sorry to say that we are not on the strongest side of this issue. We’re notable for being one of only two states in which the legislature and the governor’s office are exempt from public records requests.

Q: It comes up for debate regularly, but the law hasn’t changed.

A: Well, interestingly, whatever party is not in power is really pro opening things up, and then once they are in power, they hesitate. (Laughs.) So yeah, people have been talking about this for years and years. And it has real stakes for the ability of reporters to do their jobs and for people to know what’s going on in their communities.

Q: For large institutions that get a lot of requests, public universities included, it can be easy to think of FOIA as a nuisance. How do we change that?

A: It’s true. Not every FOIA request is made in the name of democracy. There are frivolous requests, harassing ones, excessive ones, overly vague and broad ones that are a genuine burden to our public officials. Still, I think it is a virtue that you aren’t required to give a reason to make a request. If you’re an official who is doing the right thing, if you’re educating people, serving this state, this nation, in important ways, that should be evident in the details of the released records. Not making them available, even when you’re doing the right things, cultivates a kind of secrecy that breeds suspicion and distrust.

Q: There’s been a lot written about how a lack of government transparency exacerbated the water disaster in Flint. You document the downfalls in your book, “The Poisoned City.” You also recently wrote about a lack of transparency in a different part of the state—the ongoing wait for an external review of the 2021 mass shooting at Oxford High School. How do larger government transparency issues relate to the situation in Oxford?

A: The Oxford school shooting in November 2021 was a very different kind of crisis than Flint. What’s similar is that the people in Oxford are starved for a clear, comprehensive telling of what happened, not just in the courts, which are prosecuting the shooter and his parents, but in the context of their school and the public school district that had a number of interactions with the shooter in the days and hours leading up to the shooting.

If you have a culture where the attitude is “just trust us” and you expect people to be okay with it, that trickles down to even the most locally elected, part-time, volunteer school board officials, who nonetheless are responsible for high-stakes decisions that could potentially cost people their lives. We’re creating a norm that is actually dangerous where this culture of secrecy is something we’re familiar with. That doesn’t mean it needs to be our normal.

Q: How did the fellowship prepare you to tackle this issue of government secrecy, starting with your book on Flint?

A: Well, I was a completely fried, burned out, single, full-time freelancer working all the time and feeling increasingly depleted. Without the fellowship, I don’t know how I would have emotionally been able to sustain the work of reporting and writing the book, let alone the emotional toll. Having fun with people, sleeping more, not worrying about my bills all the time, it was so restorative. And that was essential to help me go forward to finish this book and bring it into the world.

Q: What did you gain from the university?

A: It was a powerful opportunity to come at the book with resources and tools I just never had before. I took classes in the law school on water policy and environmental justice. I took an urban planning class on metropolitan structures. Visiting cities in Brazil and South Korea gave me a new perspective to think about how cities in the U.S. are made and unmade. Not having any institutional affiliation or much money when I came to the fellowship, I never had access to archives like that. Suddenly, I got this university email address and all the resources of the campus libraries, including the library at the U-M’s Flint campus, became available.

Q: And yet, you didn’t come into the fellowship with a concrete plan for what you were going to do. That makes a lot of people nervous. What advice would you give to current or future fellows who worry about having everything mapped out?

A: Some of it is just trusting yourself. Like, if you have a Tuesday, and you don’t have any classes at all, you can trust that things will show up on that day that you will learn and grow from, including just empty space, which might be the thing you need most of all.

Q: That can be a hard case to make when people’s careers feel so perilous and the industry is under so much pressure.

A: The toll this work takes—even in the best of times, let alone in these times of scarcity and threat—is so excruciating. If people are going to do this work for years and decades, well, people are not machines. We’re not machines. You need to replenish yourself. We need journalists who are whole people, who have the internal and external resources to sustain themselves for the long run. This program is so rare for truly investing in journalists, not just in what they produce. That’s an investment in journalism for the long term, not just the news cycle.

Anna Clark is a 2017 Knight-Wallace Fellow.