This article appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of the Wallace House Journal.

It was early January 2022. Wallace House Director Lynette Clemetson wrote to me to ask if I could convince the freshly minted Nobel Peace Prize laureate Dmitry Muratov to come with me to Ann Arbor to give a lecture on press freedom.

“What an amazing idea,” I responded.

Muratov is my editor-in-chief, a mentor and friend under whom I have worked for a quarter century in one of the most respected newspapers in the world, Russia’s Novaya Gazeta.

When I dialed him to propose the Wallace House event, he didn’t answer at first. We were quarreling about my refusal to evacuate from Russia after the Chechen president, Ramzan Kadyrov, called me a “terrorist” and demanded that a criminal case be opened against me. Kadyrov’s assistant had publicly threatened to “cut off my head.”

Muratov eventually called me back. “Have you finally decided to listen to your editor and leave?” he asked.

“Only together with you, and only to Ann Arbor,” I joked.

I spent the next hour telling him about my incredible year as a Knight-Wallace Fellow more than a decade earlier, about the University of Michigan where Russian poet and fellow Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky once taught. I told him about hearing President Barack Obama give the 2010 commencement address, warning that the world and professional journalism were in danger because of changing media habits – words people didn’t fully appreciate at the time. I told him about the beauty of Detroit, the catastrophic emptiness of some parts of the great American city and what it symbolized to me about civilization and history.

“I want to see it, too!” he said, greedy for such stories.

We began to make plans for a brief visit in April. But Vladymir Putin had plans of his own. On February 24, the Russian army invaded Ukraine. Three months earlier, Muratov had warned about the danger of such a war in his Nobel speech in Oslo, a war Putin had been moving toward for years. Suddenly it was happening.

Months before the war started, Putin was working to shut down the independent press.

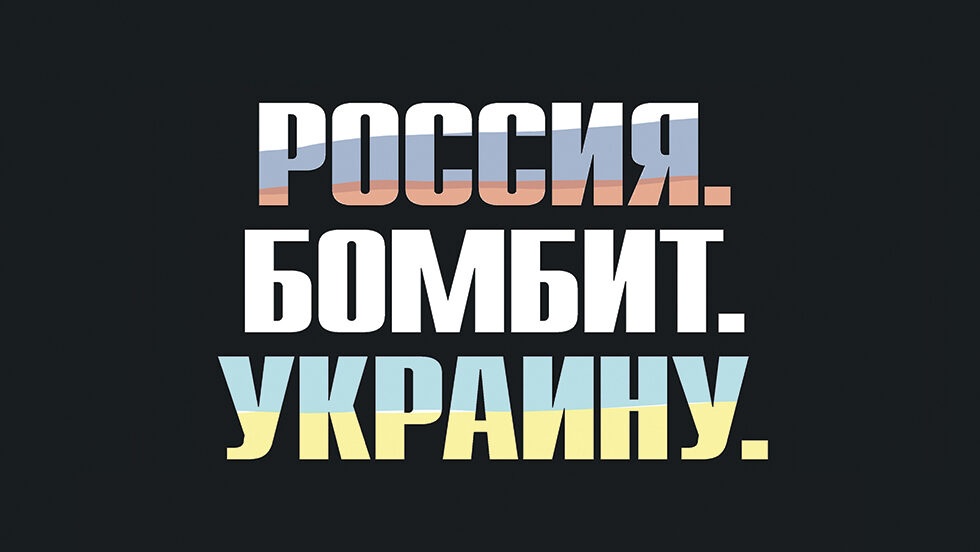

Novaya Gazeta responded to the invasion with a bold and shocking headline: “Russia. Bombs. Ukraine.”

Months before the war started, Putin was working to shut down the independent press. After opposition politician Alexei Navalny’s return to Russia and imprisonment, authorities closed down dozens of independent media outlets, primarily those engaged in investigative journalism. The government labeled hundreds of journalists as foreign agents, enemies of the state.

Russian journalists lived in anticipation of searches, arrests and criminal cases. I removed all paper and electronic archives from my house, hid old notebooks, laptops and voice recorders at my friends’ places. I thought about how I would behave during a search to make sure that no sensitive information about my sources fell into the hands of Russian police and security agencies.

Yet even in an environment of active intimidation, I was not prepared for the war and its consequences.

The government quickly came after the few remaining news organizations. In the first days of March, the last independent TV news channel, Dozhd, and the oldest federal radio station, Ekho Moskvy, shut down.

I cannot accept that I cannot write about this atrocity under my own name in my newspaper.

Novaya Gazeta held on for 34 days, the last remaining independent news operation in the country. But on March 28 we, too, were forced to suspend operations. Putin’s draconian laws imposing jail sentences of up to 15 years for journalists who reported anything the government deemed “fake news” – anyone who reported the truth of what was happening in Ukraine – made it impossible for news organizations to continue working.

Soon there was another message from Lynette. With the April event clearly impossible, she had a different proposition. “Why don’t you come to Ann Arbor for a residency, Elena?” she said. “You don’t have to leave Russia forever. But here you will be safe, and you can figure out how to move forward.”

Now I am back at the University of Michigan, a place I consider my alma mater! I am a visiting Fellow, sponsored by Wallace House, at the Weiser Center for Emerging Democracies. I will be giving guest lectures and engaging with faculty and students. And most importantly, I will have a place to continue writing. When I arrived my suitcases were mostly full of papers, unfinished work, abruptly interrupted by war. I have much I still need to write.

More than six months into Putin’s attack on Ukraine, it seems the world is beginning to get used to war. I refuse to get used to it.

I cannot accept that my country is doing this.

I cannot accept that I cannot write about this atrocity under my own name in my newspaper.

I cannot accept that my newspaper no longer exists.

Now people all over the world know Novaya Gazeta and its journalists for our journalism and the repeated attacks against us. Now Russia has made it impossible for us to exist. But we will find a way to continue.

Novaya Gazeta literally means “new newspaper.” I remember when I went to work there 25 years ago after my first year at university. I traveled around the country introducing myself and my organization and people responded, “New newspaper? So what is it called?”

Now people all over the world know Novaya Gazeta and its journalists for our journalism and the repeated attacks against us. Now Russia has made it impossible for us to exist. But we will find a way to continue.

I arrived in Ann Arbor in July, late at night. As I entered town, it was too dark to see any of the places I so fondly remembered. I had two large suitcases full of my work. I checked into my hotel, got settled into my room and began to catch up on news from the front. It was expectedly grim. It felt unacceptable to me that I had been forced to flee my country to figure out a way to report the truth about it.

But for the first time in a very, very long time, I felt completely safe.

Elena Milashina is a 2010 Knight-Wallace Fellow. She is the inaugural WCED Freedoms Under Fire Residency Fellow in the International Institute’s Weiser Center for Emerging Democracies, a position sponsored by Wallace House.